Every central bank has its ‘may day’ — the Reserve Bank too

Future interest rate hikes are no longer a given but will be data dependent

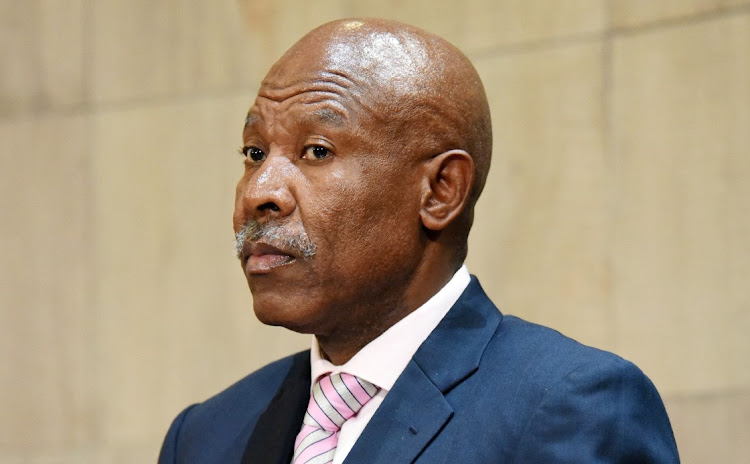

Combined with the Reserve Bank’s September monetary policy committee statement and governor Reserve Bank’s speech at the Centre for Education in Economics in September, the Bank’s latest monetary policy review signals three things.

First, it believes inflation has peaked and is on its way down. Second, demand and supply dynamics and the medium-term growth outlook are balanced, so future interest rate hikes are no longer a given but will be data-dependent. Third, the Bank has resolved to correct a 20-year policy mistake and now wants to target a lower inflation rate of 3%.

There are two monetary policy stances contained in these signals. The first two signals — peak inflation and moderating and balanced demand, supply, and growth outlooks — imply that the Bank should be pausing its interest rate hikes. The third signal — moving the inflation target to 3% from a 3%-6% range — implies that rates will need to go up a bit more to drive inflation expectations down towards 3%.

Let’s begin with the case for a pause in rate hikes. The monetary policy review says “further normalisation may be needed to raise rates to levels that are consistent with a stable and lower inflation rate”. The use of the word “may” was surprising. First, the September monetary policy committee decision to hike rates by 75 basis points was almost evenly split, with three members preferring 75 basis points while two preferred 100 basis points. This decision can be interpreted as a view still existing that more interest rate hikes are necessary.

Second, central banks are pedantic in their use of words — at times they debate the appropriateness of words such as “may”, “must” or “will” for hours when referring to their policy stance. The review’s use of “may” was therefore deliberate and implies that rate hikes are no longer a given going forward. The committee has pivoted to data dependency, as it does when the outlook is difficult to pin down.

Former World Bank chief economist Paul Romer once vowed not to sign off on any report that contained too many “ands”, because it meant excessive complication. His staff revolted and he eventually left the institution. It seems being specific with words is in economists’ genes, worse if they are members of central bank monetary policy committees.

On data dependency, the bank says demand and supply are finely balanced. This means we are in a non-accelerating inflation phase, so no need to hike interest rates if the inflation forecast is moderating towards the inflation target. Indeed, the bank’s headline inflation forecast dips back into the target band in the second quarter of 2023.

Globally, the US and Europe are expected to be in recession and China is slowing down. Commodity prices are also moderating — barring oil prices, which might increase after Opec’s decision to cut supply by 2-million barrels per day from November. All of these factors should drive global inflation down.

The case of more rate hikes is related to the need to target a lower inflation rate of 3%. This decision, as the governor’s recent speech pointed out, is 20 years late. This should have been done in the mid-2000s, but as with many other policies that were never implemented by the government, such as building electricity generation capacity over the past 20 years, it was forgotten.

The Bank has two choices to implement this lower inflation target. It will have to talk tough and hope its credibility forces price setters to adjust their inflation expectations lower, as it did from 2017 until inflation expectations adjusted to 4.5%. If this fails the Bank will have to hike rates to demonstrate its commitment to lower inflation to 3%.

There is no better time to do this than now. Why drive inflation expectations back to 4.5% and not to 3% when the sacrifice ratio is so low as to be insignificant?