Reserve Bank’s murky messages over rates move hurt confidence

The market expected a cut after messages by monetary policy committee members on various platforms

Communicating with ruthless clarity is always preferred in economic policy as it influences the expectations of market participants. Policy direction, or in central bank parlance “forward-guidance”, can build or destroy confidence, which is necessary for SA’s economic recovery after all the recent negative shocks.

In times of crisis, clarity of communication is even more crucial to dampen volatility, in addition to influencing the formation of expectations. The Reserve Bank monetary policy decision announced on September 17 was one of those in which better communication could have reinforced market confidence, but it instead left me and some other market participants with many questions.

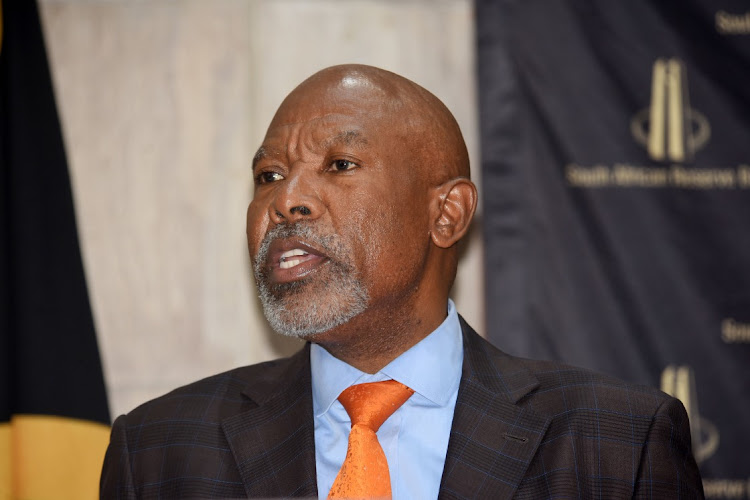

In the run-up to the September meeting, a number of monetary policy committee (MPC) members communicated on various platforms, the overall effect being that the market expected the Bank to cut interest rates. Two such members stand out: Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago and the bank’s head of research, Chris Loewald. In some of his speeches, the governor clarified the use and conditions for bond-buying programmes, commonly known as quantitative easing, which I believe resulted in less noise over the issue in recent weeks.

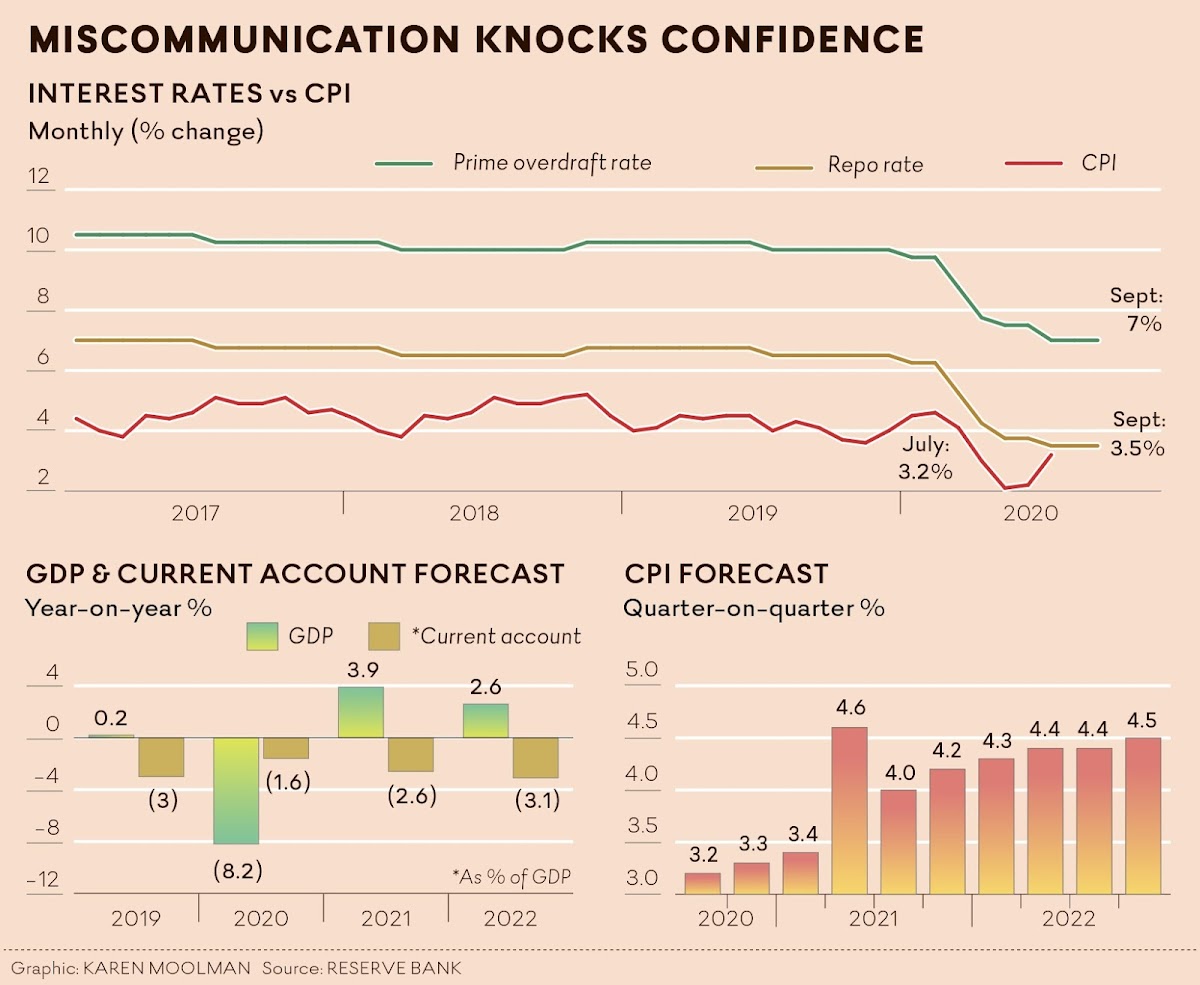

Kganyago also reiterated that the Bank has been one of the most aggressive central banks in its response to the crisis in terms of interest rate policy, with the repo rate cut by 300 basis points since the beginning of the year. He has also put the ball in the Treasury’s court to do its bit by emphasising that if fiscal sustainability were to be guaranteed, the Bank could do more to support the economy. On this, the jury is still out. The governor has always emphasised that monetary policy alone cannot solve SA’s growth problem, a view I share.

The overarching assessment of Kganyago’s recent communication is that he believes monetary policy has responded adequately to the demand shock, which is what monetary policy is about, and the Bank should not be drawn into trying to respond to supply-side constraints as this would have limited to no effect. He is likely to have been one of those who preferred to keep rates on hold at that meeting.

In times of crisis, clarity of communication is even more crucial to dampen volatility, in addition to influencing the formation of expectations. The Reserve Bank monetary policy decision announced on September 17 was one of those in which better communication could have reinforced market confidence, but it instead left me and some other market participants with many questions. In the run-up to the meeting, a number of monetary policy committee (MPC) members communicated on various platforms, the overall effect being that the market expected the Bank to cut interest rates. Graaphic: KAREN MOOLMAN

Output gap

Regarding Loewald’s recent communication, he was clearer that monetary policy had more room to cut rates. Some in the market believe that could have driven market expectations for a cut the Bank did not deliver, and that consequently constituted miscommunication. I disagree.

MPC members are not a homogeneous group of policymakers; they do not see things identically and they do not have to have the same view on the appropriate policy response. If they did, we would need only one person to make the decision. That diversity of views is what makes the committee more robust. To formulate expectation about what the policy path will be based on an individual policy member misses this point.

The one big issue that emerged from the MPC statement was that of the output gap. The Bank revised the output gap lower, all the way from 2017 to 2022. The revisions were bigger for 2019-2022, amounting to half a percentage point for all years except 2021, when it was 0.3 of a percentage point. Three issues are associated with this.

The revision to historical estimates of the output gap that result from the downward revision to potential economic growth is troubling. No new information is available now that was not available at the last MPC meeting that would indicate potential economic growth was likely lower in 2019 than the previous estimate suggested.

Second, the revisions were made based on a statistical output, since potential economic growth is an unobservable variable. However, given the economic shock that has been created by Covid-19, no assessment has been explicitly made to the effect that it will have a permanent impact on potential economic growth. If that assessment has been made, it would be premature anyway. Econometric modelling is both science and art. The science is the robust mathematical representation of the economy, which is never precise on aggregate because most economic variables are either estimates or cannot physically be measured accurately. The art is where judgment comes in.

Inflation forecasts

If there are temporary shocks to the economy, judgment should have been applied to ignore the shock from Covid-19 such that potential economic growth should not have been significantly revised lower in such a way that narrowed how wide the output gap is compared with the last MPC meeting in July. In estimating the output gap, the Bank seems to have forgotten to apply judgment, and instead chose to follow a rigid statistical methodology that is known to have shortcomings — the famous endpoint problem.

Third, growth was revised lower for 2020 and 2021. So was inflation, though only marginally to 3.3% in 2020 from 3.4% at the previous MPC meeting. Inflation for 2020 was revised to 4% in 2021 from 4.3% previously, even with a narrower output gap. The question is what inflation forecasts would have been had potential growth and the output gap not been revised this much, and what the policy consequences would have been. It is likely that the inflation forecast would have been far lower, compelling the Bank to cut rates.

Even with lower inflation forecasts that would have resulted from no revision in potential economic growth and the output gap, the Bank could still have decided to keep rates unchanged and rather communicate the decision better. For instance, it could have used the fact that much of the policy decisions are still filtering through the system and say, as a result, it chose to wait to see the impact. It would have been perfectly reasonable to keep rates on hold, rather than to miscommunicate the role of a statistical model, which needed more judgment but that the Bank seems to have overlooked.

The Bank’s main model, the quarterly projection model, projected interest rate hikes of 25 basis points in the third quarter and fourth quarter of 2021. The MPC has stressed that this is policy guidance and not a predetermined path. However, at past MPC meetings, the Bank has decided to bring forward that policy guidance and administer rate cuts when the model suggested cuts in the quarters ahead. It will be interesting to see if this decision is symmetric when the model suggests interest rate hikes, especially if inflation risks are assessed to be on the upside.