The Bank would be right to move to a 3% inflation target

It might be painful for some time, but the long-term benefits make it worthwhile

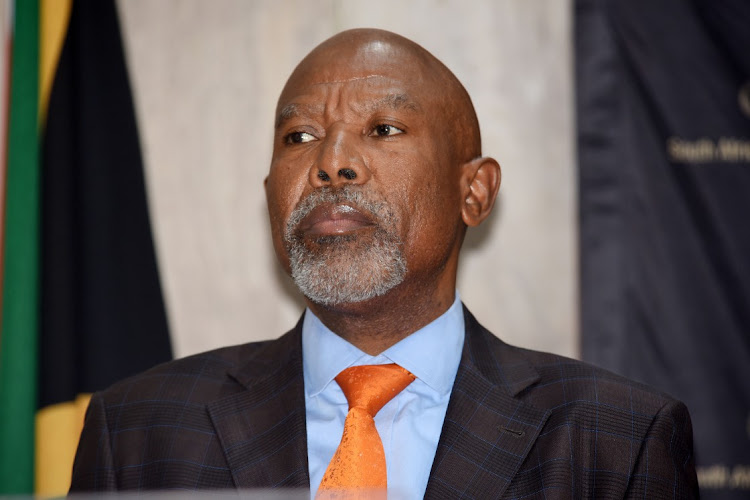

In a public lecture at the University of Stellenbosch on September 8 SA Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago revealed that the Bank wants an inflation target of 3%.

I believe the Bank is on a Paul Volcker wicket, and if it implements this natural progression in policy this will go down in history as one of the three policy choices SA got right in the management of the rand, the other two being to end the financial rand system in 1995, and to adopt the inflation targeting framework in 2000.

Volcker was an economist who served two terms as chair of the US Federal Reserve (Fed), under presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, between 1979 and 1987. This was a period in which US inflation fell from 14.8% in March 1980 to 3% by 1983.

To bring that inflation under control the Fed funds rate was increased from an average of 11.4% in August 1979 to a peak of 20% in May 1981. The economy contracted, and the unemployment rate rose to more than 10%.

These developments inevitably had political fallout, and led to an attack on the Fed and widespread protests. But once inflation had declined interest rates also declined, to a low of 5.9% in August 1986. Since then the highest the Fed funds rate has reached was 9.75% in late 1980, and 6.5% since 2000, with peak average inflation of 5.4% in 1990.

The link is obvious, as Kganyago alluded to in his speech — low inflation results in low interest rates, and it’s the same in every properly functioning economy.

Since the governor’s speech there have been two strands to the debate taking place on monetary policy. Those who associate with heterodox economics say this move by the Bank is bad, and in fact we need a higher inflation target so that interest rates can be low to stimulate economic activity. Or so they argue.

This grouping has been pushing for lower rates and a higher inflation target for quite some time. However, this line of thinking is not supported by any concrete evidence outside of isolated coincidences that cannot be deliberately replicated.

The other argument, surprisingly, comes mainly from professional economists, who maintain that it is appropriate to lower the inflation target to 3%, but not now given the effect of Covid-19 on the economy. That’s almost like sailors saying because there are tides in the sea they need to wait until it’s tranquil before they can set sail to a desired destination.

Tranquility is never guaranteed. To use a different example, it is similar to deciding to amputate a broken leg because fixing it might be a bit painful for a while. In truth, amputation causes lifelong disability.

In 2004 government decided to amputate monetary policy’s legs by not reducing the inflation target as initially planned, because of concern that adjusting to the weak currency in the wake of the Argentinian crisis would be a painful process. We remained with an effective target of 6% until 2018, when the Bank explicitly said it would prefer inflation to be anchored at 4.5%.

In the years that followed, better communication combined with modest interest rate increases totalling 200 basis points, from 5% in July 2012 to 7% in June 2017, allowed the Bank to push inflation expectations down to 4.5%. Since the peak in June 2017 the repo rate has been declining, to the current record low of 3.5%.

Technically, I would argue that the Bank does not need the government’s approval to target 3%, much like it did not need the government’s approval to anchor inflation expectations at 4.5%. And 3% is the lower band of the target range of 3%-6%, so the Bank can target it without any change in the framework.

It follows that the Treasury must speed up the formalisation of a point target, and provide support for the achievement of a 3% target over the medium term. Inflation expectations can be driven down with more communication and modest normalisation of interest rates.

In any case, interest rates will have to normalise in the next three years whether the inflation target changes or not.